Freeze Magazine: Borrowing is Better Than Being Original

In the sprawling world of meme culture, a handful of voices stand out for their witty takes, creative originality, and keen ability to tap into the zeitgeist of the internet age. Cem A. is the memelord behind the immensely popular account @freezemagazine, a space that wittily navigates the nuances between contemporary art and the internet's ever-evolving meme culture. Recently, I sat down with him for a candid conversation that traversed the diverse terrains of art exhibitions, magazines, the intricacies of meme-making, and the impact of real-life issues on artistic expression.

Nat: Hi Cem! How are you?

Cem: Doing good, thanks. Do you mind if I keep my camera off?

N: Not at all. I’ll turn mine off too. So, I’m really interested in the inner workings of your meme account and the memelord behind it.

C: Thank you. What would you like to know?

N: How were you as a kid?

C: I was very interested in cartoons — both children’s and political. I guess it’s related to making memes now. The most haphazard things I've been interested in have found a place in my memes in really unexpected ways.

N: Did you ever try creating your own cartoons?

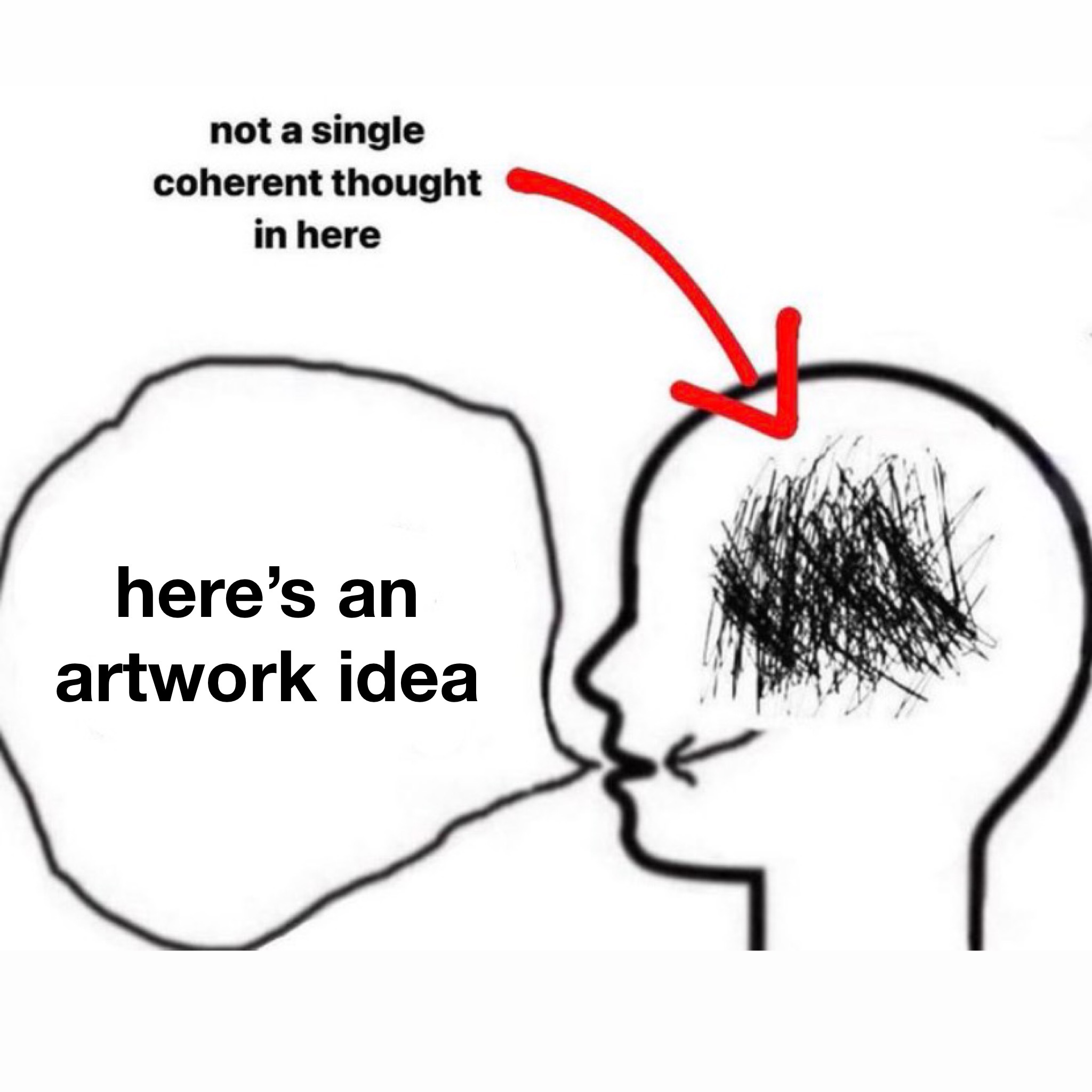

C: Yeah, I wasn’t very successful. Memes speak in a different way. It’s okay to not be 100% original. I find that very nurturing and interesting as a concept.

N: I like imitation too. It’s funny when people claim originality so desperately but whatever they’re making or doing is always the reincarnation of something else — whether they know it or not.

C: And to build on other people’s ideas or to riff on other people’s memes and creations is much more interesting to me.

N: So how was @freeze_magazine born? Were you imitating someone?

C: It wasn’t such a conscious decision actually. I had finished university and was looking for a job. It was hard because I was in London, I’m not an EU citizen, and needed a visa sponsorship. So I started the account to channel my frustrations. It was more about me doing it every day without taking it too seriously, never like a grand project.

N: I saw on your website that you studied anthropology. Does that reflect on your practice?

C: Yes, definitely. I like to see making memes as a form of artistic field research. I don't want to only focus on contemporary art markets or art criticism, so anthropology helps me gain a different perspective.

N: What do you think is the lifespan of digital meme culture? Is it going to end?

C: It depends on how you define meme. There is a distinction between memes in general, and internet memes specifically. Internet memes are constantly evolving and it can be hard to keep up with the changes; from action memes to maniac memes, and now even sound memes on TikTok. I think they’re evolving into something more sensory, experiential, and multimedia, but they’re not going away.

N: Are you familiar with Joshua Citarella?

C: Yes, we actually met a couple weeks ago for the first time.

N: I read this article on Do Not Research called How to Plant a Meme where he basically said that to plant a meme you must make hundreds of small accounts that post about whatever you want to memefy and have it slowly trickle down into the big accounts. Is that true?

C: It's hard to tell because there's a meta element to the project. You can make an argument for both sides: it's unrealistic for an individual to make so many memes and post on so many accounts, but you could also just petition people to make them.

N: Is that what you do?

C: No. For me it’s more about talking about the subject rather than making the meme template. Something new I’m doing is called “situated memes” which is this idea where I try to create physical extensions of digital memes. I just posted one on my account a few minutes ago.

N: Oh, is it the candle?

C: Yes. I made this meme a couple years ago about these glass jar candles and came up with fake scents for them, like Exhibition Opening. Now, I’m producing actual candles as a joke, to build on that. So I’m materializing digital memes. I’m also creating situations and installations in physical spaces that could be memefied. It’s a very abstract process.

N: So the “they don’t know lighter” is also a situated meme?

C: Exactly, it’s an extension of the meme, not a representation of it.

N: I saw the exhibition you did in Istanbul. What a smart way of shitting on the art world.

Cem laughs.

N: Did this real life collaboration stem from the collaborative nature of meme making?

C: For sure. I’m interested in what others are doing and I like to recognize their contributions. Being a part of documenta taught me the benefits of collaborative work, which I applied to the exhibition in Istanbul. For this show, my main purpose was to create exhibition text so generic, that it could apply to any show. I asked writers and curators in the field to help me write a generic exhibition text, and included their thoughts in the final product.

N: It made me think that we’ve been forced to respect art through shaming. Exhibition texts are full of jargon, designed to make you feel stupid. So when you don’t understand the text, some people assume that the art is on another level and that they’re too dumb to get it. Your show invites viewers to take art less seriously.

C: Thank you. To me it’s about not taking yourself so seriously but also about how arbitrary these things are and how art is viewed as a mechanism to turn arbitrary stuff into something conceptual. No one is allowed to question this or engage with it directly. It always has to be indirect, in both describing and communicating what you do and also reacting to what others do.

N: Are you familiar by chance with a gallery in Istanbul called Viable?

C: No, tell me about it.

N: They have a small space called Yaya. It’s literally the smallest gallery I have ever been to. They have this storefront, basically just a window display, inside this antique sort-of-mall in the middle of Cihangir. You can only look at the work from outside the window because people don’t fit inside the gallery.

C: Oh, I’m looking at it now and I know some people involved with it.

N: My friends own the space and they made it because they wanted to show good work. And that’s what they’re doing. Attending art openings is another indirect aspect of viewing art. It’s about being seen there. At Yaya, it’s only about the work. There’s no seriousness about it at all.

C: For me the problem isn’t only the seriousness but also the indirectness. When things are so removed, it’s so hard to engage closely with a subject and you don’t get the space to be unserious or even serious, ironically. Some art must be taken seriously too. The dialect and the etiquettes surrounding institutions are getting in the way of serious art.

N: What do you think is art today that must be taken seriously?

C: What’s happening in Iran, for example, that type of art is lagging. Because of the institutions and what’s expected of them, it’s much easier for them to engage with a political incident that happened 30 or 50 years ago. But they also have so much responsibility for what's happening right now in other countries. People are hurt, killed, imprisoned, literally every day because of this so I think that the art world has a lot more responsibility for this than they admit.

N: So you want the art world to take responsibility for some of the controversies that they are causing?

C: I’m trying to imagine new forms of art making that allow for immediate reaction to political events that actually matter. It was the same in the US with this whole thing about the rail workers that were denied sick leave, and how the government completely busted this and denied the strike to the people. I find it unimaginable that this can happen in a first world country. There is no space to gather around this issue.

N: Part of the issue is politicizing things that have no political standing in the first place. This takes space away from real issues that should be part of the conversation. It’s hard to know when people are being sincere or when they’re playing a part. Are you sincere?

C: Yes, I’m trying for sure.

N: Me too.

Cem A. is an artist and curator with a background in anthropology. He is known for running the art meme page @freeze_magazine. Selected exhibitions include documenta fifteen, Kassel (2022) and solo exhibitions Hope You See Me as a Friend at Barbican Centre, London (2022); Pleased to Announce... at Versus Art Project, Istanbul (2022) and The Party at Weserhalle, Berlin (2021). He has held lectures at HeK Haus der Elektronischen Künste, Basel; Universität der Künste, Berlin; Royal College of Art and Central Saint Martins, London. His work has been featured in The New York Times, The Art Newspaper and Dazed Magazine.

Nat Ruiz is an artist and designer living in Portland, Oregon. She is the creative director at Forever Magazine.